19 Jun Three years of river rights: Collective Agency for Community Ontologies on Water

Blog Series “Nature and Its Rights”: Young researcher´s seminar April 2020

By María Ximena González Serrano (Guest Author)

Lee la versión en español

It´s been three years, as of May 2020, since the publication of the decision that recognized the rights of the Atrato river. This ruling was a link in the chain of decisions adopted in 2017 in three countries in the world, whose legal systems assigned rights, and legal status in degraded rivers or rivers that are under serious environmental threats. These are: Atrato in Colombia (Constitutional Court, Judgment T-622 of 2016); Whanganui in New Zealand (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) and Ganges and Yamuna in India (Salim v. State of Uttarakhand, Writ Petition No 126 of 2014).

Image 1: A believing woman raises a prayer to the waters of the Yamuna-India river (2017)2

Worldviews and communitarian cultural practices: source of law

These are coincidental cases that embraced a formula for subjective protection of nature, based on expansion of Western law to other ways of conceiving water and rivers. These precedents occurred in response to the activism of judges and legal operators, which went beyond the repetitive recipe for sustainability and water governance. However, from my perspective the most remarkable side of these cases is the substantial leading role of traditionally excluded ethnic and local communities. Their worldviews and territorialized knowledge were part of the argumentative background of the decisions. The rights of people and communities appear as a creative source of new water protection mechanisms.

Image 2: Members of the Maori people Iwi and Hapu, original claimants of the Whanganui River –NZ3

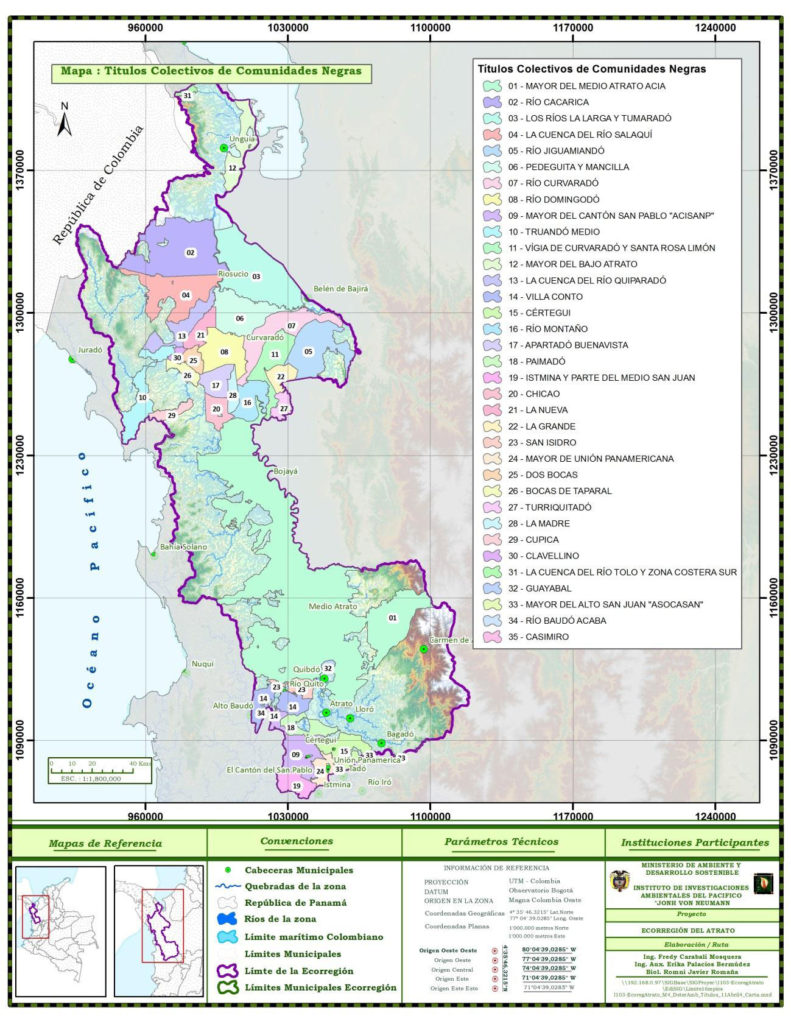

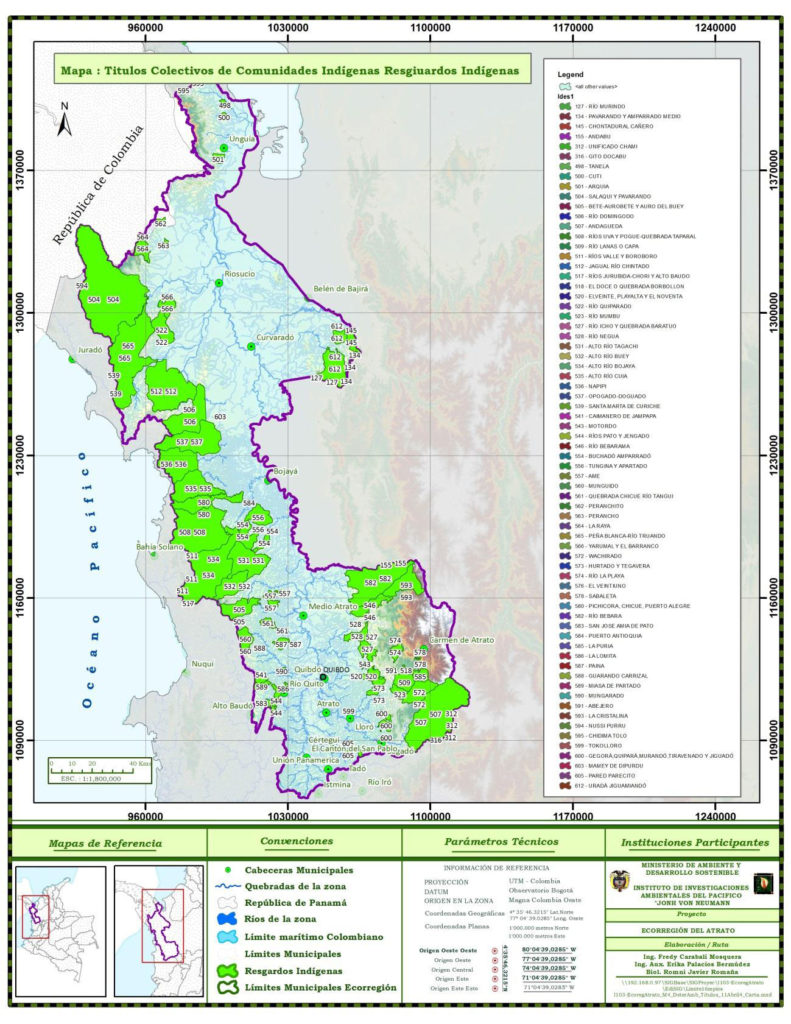

In the case of the Atrato river, the Court based its judgment on the recognition of the relational and systemic character between the river and the afro-Colombian, indigenous and mestizos’ communities that inhabit it. Through biocultural rights formula, the historical and daily interdependence between the communities, the river, and biodiversity were taken into account, recognizing the existence of knowledge and life practices of high importance, but also of disruptive factors that must be reconsidered.

The Tribunal declared the existence of a new subject of rights, as a mechanism tied to the guarantee and restoration of multiple rights that were violated among the communities.

The foregoing, is of enormous relevance, since the recognition of rights to a non-human subject was leveraged based on its connectivity with the communities that develop their life around it. So it is not a self-absorbed protection of the river, which aims to separate human communities from the very concept of nature, but contributes in its symbiotic understanding.

Map 1: Atrato River Ecoregion – Collective Territories of Afro-Colombian Communities

Source: Ministry of Environment and Pacific Environmental Research Institute 2019

Map 2: Atrato River Ecoregion – Collective Territories of Indigenous Communities

Source: Ministry of Environment and Pacific Environmental Research Institute 2019

Human Rights and rights of nature: a necessary interrelation

The mutual relation between human communities and nature is important for rethinking the very concept of “rights”. We can ask ourselves whether nature rights and river rights compete or if they are articulated with the human rights framework. The following question may be explanatory: Do the new agreement scenarios that have been created to guarantee river rights, diminish the weight of rights to life, personal integrity, health, education, food, prior consultation, and free, prior and informed consent of ethnic communities of the Atrato? This question has considerable repercussions since the decision to grant rights to the river did not silence the rifles, nor did it end the dispute over the territories by multiple players and interests.

In the words of Leiner Palacios, Afro-Colombian leader of the Bojayá community, located on the banks of the Atrato:

“2018 and 2019 have been years of hell again for the communities in Bojayá. There have been multiple confrontations, confinements and murders (…) And they are really having a very bad time. Today, Bojayá is a zone of hell and war (…) The other element is that in Bojayá there are economic interests. It is a territory rich in biodiversity and natural resources. Since the State does not provide rights, this forces people to leave the territory and thus it gets empty”.

Click: To view complete interview

Factors of socio-ecological disturbance and serious violation of the rights of the population remain intact on the river. What does it mean to have a river with rights in a region devoid of the minimum guarantees for the lives of its people? What does it mean to separately conceive the defense of water, the environment, and the river, with the overcoming of violence and the eradication of oblivion and exclusion policies? Without an integrating view of these agendas, the plans that have been built in compliance with the ruling will be a new letter of promise and not a roadmap for transforming visions and realities.

The declarations of river rights should not blur or pale the meaning, validity and need for human rights, on the contrary, emerging scenarios should be a platform for their realization. However, it is also imperative to fill the rights of rivers with philosophical, normative and institutional content so that they do not become a decorative washer of the rhetoric of a few.

Social and community processes: their role in the declaration of the river as a subject

The prominent role that local communities have played in the emanation of these new decisions to protect nature and rivers, is also evident in the organizational strategies that preceded the ruling and the law, as well as in the new spaces configured for compliance. In the case of New Zealand, the fight to demand that the Whanganui River be legally conceived as a living entity took 147 years. However, in the case of India, the legal defense of rivers and glaciers was not linked to a process of collective action by the riparian populations, but to litigation in the public interest. And possibly, that was a symbolic reason that facilitated their subsequent revocation by the Supreme Court.

In the case of the Atrato, the defense of the river was part of a broader organizational process with several years of experience. Two milestones served as background: The first one was the social mobilization known as “Atratiando: for a good deal with the Atrato”, a civil resistance act organized in 2003, with the aim of raising awareness of the systematic violence in the region, which left more than 60,000 displaced Chocoans.

It was a community pilgrimage along the river. The communities, social and church organizations, organized a commission of boats that traveled a good section of the basin for five days, challenging the political and military control exercised by paramilitary groups. These criminal organizations blocked the free transit of people, food, commerce and medicines for 7 consecutive years, with the aim of generating high armed violence and social pressure to force the massive abandonment of the territory and its subsequent appropriation.

As described by González:

“The ‘Atratiando’ set a fundamental precedent, provided it raised some crucial messages: the Atrato does not belong to arms, the river is for everyone, the river is life and well-being for communities, and the people of the Atrato will join as many times as necessary to protect their river, protect their life. ”

Image 3: Community river mobilisation in the Atrato: a good deal for the Atrato (2003)

Source: Steve Cagan. Click to view full gallery

The second milestone was the 2015 “Regional and Inter-Ethnic Peace Agenda for Chocó”, a document that included the main proposals of the department’s social movement. Its construction was based on an articulation work that involved a large number of ethnic and civil society organizations, in which the fundamental lines of how life should be in the region were projected. One of its transversal axes, called “Territory and social and legal enforceability”, set the framework for the legal enforceability strategy in defense of the Atrato (To learn more about the Chocó Regional and Inter-Ethnic Agenda for Peace, see the following link).

Rural populations of Chocó, as well as other ethnic or local populations, can not only be seen as victims or marginalized. They are people with enormous resiliency, with a powerful collective memory that allows them to face and cope with adversity and to undertake advocacy processes with an outstanding impact (To learn more about the community process in defense of the Atrato, see the following link).

Image 4: Community School of Guardianas del Atrato – Chocó (2019)4

The defense of the Atrato has also been an engine of new dynamics and interactions within the community processes. It has been an opportunity to see themselves. The understanding that what happens or what is decided upstream also affects downstream and the awareness that they depend on each other to survive and remain has strengthened their voice, their cohesion and their capacity for collective agency.

The sentences of rivers with rights are legal instruments that allow us to reflect on the territorial, population and ecosystem connectivity around water. They lead us to see traditionally excluded populations that offer us key elements around fundamental transformations with their knowledge and ways of life with a different perspective. The great challenge for this vision is to permeate the construction of policies, public debates and decision-making spaces and to materialize in deep and concrete changes that benefit the environment and the most vulnerable populations.

The recording of the two webinars of the “Nature and and its Rights”: Young researcher´s seminar June 2020 is available at: rivers-ercproject.eu/media

About the Author: Lawyer, she holds a Major in Environmental Law, with a Master’s Degree in Latin American Studies. She worked for 15 years with indigenous, Afro-Colombian and peasant communities in defense of the territory, water and rivers in Colombia. She was co-founder and co-director of the Tierra Digna Center for Social Justice Studies between 2010 and 2018, from where she accompanied the Atrato river defense process. Currently she is starting her doctoral research project on river rights.

2 Image available here

3 Image available here

4 Image available here