12 Jun A dying river in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala

By Rachel Sieder and Lieselotte Viaene

Read the Spanish version

Un Río Que Muere En Alta Verapaz, Guatemala …..

“The hills began to emerge from the water

and at once they became great mountains.”

Popol Vuh

In June 2019 a video circulating on Facebook showing the disappearance of the San Simon river in Chisec, Guatemala, known for its tourist attractions, provoked an avalanche of reactions of dismay. According to public opinion, the death of the river was because it had been diverted by one of the many extractive projects operating in the territory of Alta Verapaz. Hydroelectric plants, African palm plantations, farmers and logging companies were all publicly accused of stealing the river, of rivercide (ríocidio), or ecocide.

The following day, the Guatemalan newspaper El Periódico published a press release from the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) stating that the river’s disappearance was a “normal” event caused by the prolonged drought in the region, natural effects that should be attributed to climate change.

“New” and “old” violence in Alta Verapaz – Guatemala

Before the arrival of Catholicism in the 16th century, Alta Verapaz was known as Tezulutlan or land of war. Today it seems to be a site of new planetary wars, in recent years becoming one of the epicentres of disputes over territory in Guatemala, and particularly over water. Its mighty rivers, including the Cahabón and its tributary Oxec have attracted hydroelectric energy projects, unleashing notorious conflicts, such as those over the Renace and Oxec projects. The rivers have been fragmented and year after year they have dried up. Many farmers have sold their lands to multinational companies promoting mega-projects.

Cardamom, which was extensively cultivated in the 1990s, has been replaced in part by African palm, a thirsty monoculture that monopolizes water sources wherever it is planted and also contaminates the little water that is left for the local population. The environmental protection and management plans of large projects have often proved to be highly deficient. Added to this capitalistic plundering, population growth combined with the increasingly marked effects of climate change have further exacerbated disputes over resources in this region, where poverty rates are among the worst in the country. The resistance of the Q’eqchi’ and Poqomchi’ people to encroachment on their historical territories has led to the criminalization of community leaders, who have faced arrest warrants or even imprisonment, as in the infamous case of Bernardo Caal Xol. Other leaders have suffered open repression, including death threats, physical attacks, and even assassination.

Sadly, the suffering of the indigenous population in Alta Verapaz is nothing new. The cost of the internal armed conflict of the 1980s and 1990s was incalculable for the Q’eqchi’ and Poqomchi’ inhabitants of this region, who suffered massacres, mass internal displacement, and the enslavement and brutalization of women and children by military forces. Exhumations at the CREOMPAZ military base in Cobán have revealed the largest clandestine mass grave in Latin America. The army not only violated people’s most fundamental rights, but also committed muxuk, rape or desecration against the nature of everything. The Q’eqchi’ talk about the war as nimla rahilal, the great suffering. And as many community members have said, socio-environmental conflicts over extractive projects are the new nimla rahilal.

A multidimensional analysis by the Q’eqchi’ elders

The video of the vanished river made us revisit what we had both learnt in Q’eqchi’ territory, more than anything else the deep and intertwined relationships that exist for Q’eqchi’ between human beings and non-humans, expressed both in their ontology and their daily practices.

In April 2017 we spent a month in Nimlaha’kok, a village in the Cobán municipality that we had both visited years before in the context of different research projects. This time one of the interests that brought us back to this small village was to learn about the relationship between the Q’eqchi’ and water, particularly from the knowledge and memory of male and female elders.

When we arrived at the village there was almost no water: a small stream below the community served most of the families and it took hours every day to bring the vital liquid back to their homes. We recycled every drop of water, aware of the tremendous scarcity which villagers told us was getting worse every year. Finding a dead rat in our kitchen sink caused a small crisis because it meant emptying the sink completely, washing it out, and bringing several gallons of water up again from the stream.

Natural spring comunity Nimlaha’kok, Alta Verapaz. Photo credit: Rachel Sieder and Lieselotte Viaene

In different collaborative workshops, the elders shared their knowledge. They told us that in the past they were more in contact or communication with water: “We used to greet the water every day when we went to the mountain to collect it…we were in communication with the water, with the stars”. They used to undertake the mayej, the ceremony to ask for permission. As one woman elder put it: “we were paying (tojok) with pom (incense) and candle to the water, to have permission to use it”. The reverence and care for water, a being, as they said, who never sleeps, was evident.

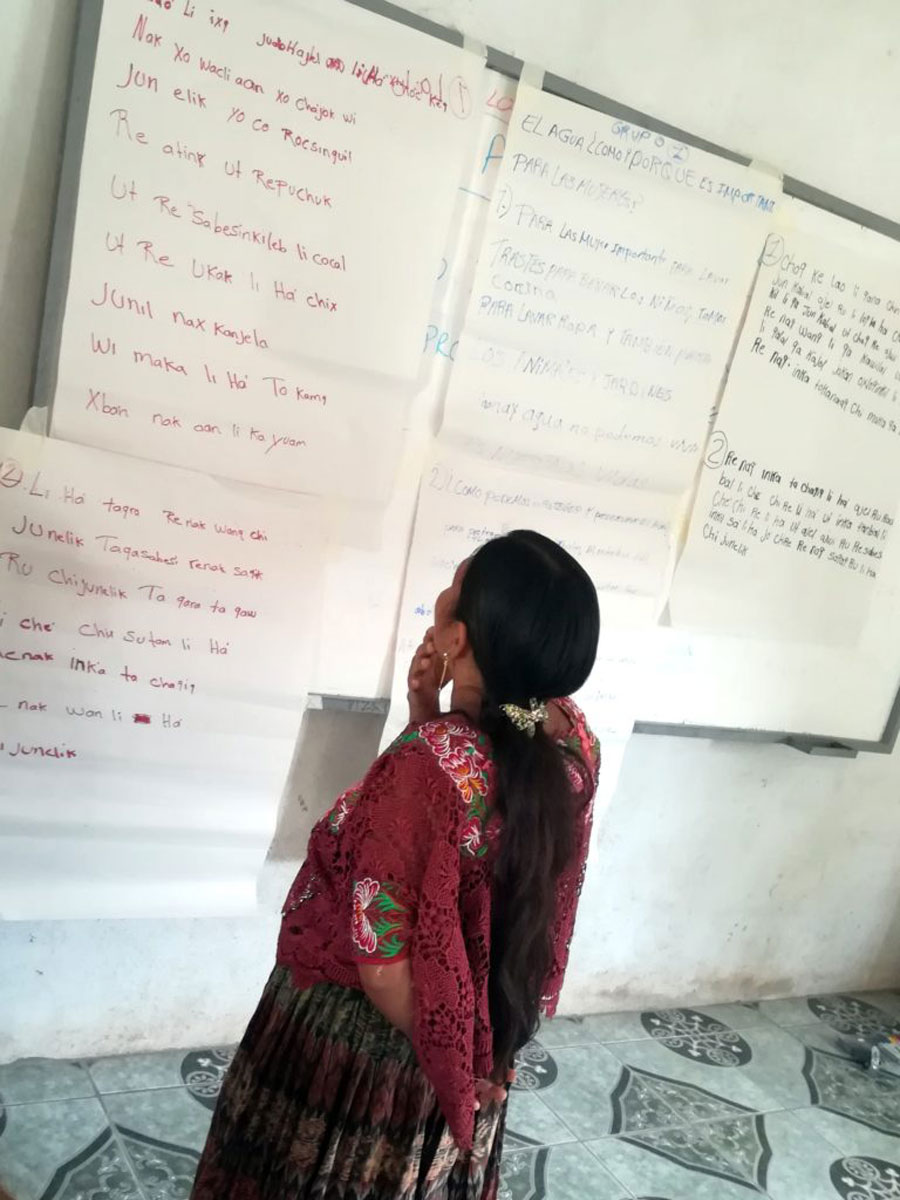

Workshop about wáter with q’eqchi womenPhoto credit: Rachel Sieder and Lieselotte Viaene

One woman elder told us “my grandmother carried a candle and pom to ask the water’s permission, so that people and water would not feel shocked when they met. The grandmothers said you must greet the water. Cho na, so that it doesn’t get scared. There were words you had to use to greet the water before you started your day.” The perception of water and rivers as living beings was clear. As Qana Elvira told us: “the river has a heart, it lives, it has veins. My grandparents used to say, the veins are like the streams that come out of the big rivers. Water is the sweat of the earth. It does have a heart. If it didn’t, it wouldn’t be alive.”

Multiple reasons were identified for the water crisis they were experiencing in Nimlaha’kok, from lack of everyday care to the impact of mega-projects. The women elders lamented the effect of the changes: “Now water comes to the houses in pipes, we no longer greet the water”… “Young people do not know the sacred sites of the river so they do not ask for permission and they violate the life of the river (xmux’bal yuam nimla ha)”. They recognized the negative effects of population growth and contemporary habits, saying that villagers cut down trees close to the springs and observing pollution, “from plastics, soaps, pesticides, garbage.”

Certainly, if before there was an abundance of macuy, now the widespread use of pesticides has destroyed the wild plants that previously supplied the daily diet of tortillas and beans. For Qawa Flavio a clear logic underlay the scarcity of water: “Water is withdrawing because of deforestation. We’re killing the water ourselves.” Pollution and negligence hurt the water: “that’s why the water gets angry, that’s why the community stream dried up. As a living being, “water sends us this sign that it is not happy, that it is sad”.

The elders said it was partly a problem of education and intergenerational transmission of knowledge: “We are all guilty, we do not tell the children how to take care of the sacred water…these ideas are hard to speak about and to understand, young people do not believe us”… “why should children say good morning to the water if it comes from a pipe? When we were young we had to go to the hill to get water, it was a law to greet the water. Now young people don’t respect those ideas, they don’t want to listen…they make fun of us, everything has changed”.

However, as the global crisis of climate change indicates, reverence and care for non-humans is vital to keep them alive. As one Q’eqchi’ elder explained to us, “when you go to a sacred place, you are not going to make a mess, to sully it. You have to go there asking permission, respecting it as if it were a person.” As we know, capitalist commodification clashes deeply with the millenarian concepts at the heart of indigenous worldviews, and not only in Guatemala. But there is no doubt that current patterns of capitalism must transform in order to counteract the effects of climate change, increasingly acute effects that endanger our survival, along with that of other species.

Workshop Q’eqchi elders , 2017. Photo credit: Rachel Sieder and Lieselotte Viaene

The boom of mega-projects in the region and their effects were also discussed with the elders in the Nimlaha’kok workshops. They all conveyed to us images of destruction and loss. “Now they are cutting the veins of the earth because of the construction of the hydroelectric plants” Don Zacarías told us: “If they cut the river it will dry up. It’s as if the blood in your body dries up, it’s similar to what happens with water.”

Workshop with Q’eqchi women elders, 2017. Photo credit: Rachel Sieder and Lieselotte Viaene

Our own anguish about not having water was shared by all. Qana Herlinda told us: “when I grew up there was a lot of water, the little springs never dried up. There were so many fish, that’s where we fed ourselves. …they are already blocking the rivers, they are pouring poison into the rivers. We don’t respect each other, but we are all the same, children of one God. They’re saying that one day the water will run out, that it will only be possible to buy it by the barrel. I’m a widow, how am I going to do that? I can’t afford it.”

The fear for the world that future generations would inherit was perhaps the most striking aspect of the workshops. As a woman elder plainly stated, “Water is the centre of life, the centre of everything, our children and grandchildren need it. Without water we cannot live.” Women were in daily contact with water and felt its absence more acutely: “water is a life partner, like a husband, it is my partner every day. Without it we cannot live, it is part of our life.”

The legal revolution of giving rights to rivers: a patch over a wounded planet?

Since 2017 there has been much international interest in the possibilities that the attribution of legal personality to rivers can offer to combat the environmental crisis. New Zealand, Ecuador, Colombia, India, Argentina, and Australia have declared rivers as subjects of rights in innovative legal decisions enshrined in new laws and rulings. These rivers now have the status of living entities and are considered legal persons, with their corresponding rights, obligations and responsibilities. For now, Colombia is at the forefront of this legal revolution with three rulings for the cases of the Atrato River (2017), the Coella, Combeima and Cocora Rivers (2019) and the Cauca River (2019). The common objective is to ensure the protection, recovery and conservation of these rivers, all severely polluted and/or altered by mining or hydroelectric power. To combat climate change, last year Colombia also recognized rights of the Amazon and the Pisba moorlands.

This emerging “ecological jurisprudence” exists thanks to legal actions by communities affected by extractive projects and their allies, which is contributing to the global trend of a recognition of “Earth/Nature rights”. A key seedbed of this new legal trend was Ecuador’s constitutional recognition (2008), the first in the world, of Nature as a subject of law. In fact, this issue is not so new: by 1972, law professor Christopher Stone (University of Southern California) had already posed the question of whether trees should have legal standing.

Climate change requires new legal tools. It is urgent to rethink the subjects of rights by questioning their anthropocentric origin. As a Mayan lawyer colleague told us: “we must rethink human rights from their origins – water, fire, earth, our elements. If these don’t exist, we don’t exist. We must rethink the right to life using all the elements”.

However, in the face of international enthusiasm about these legal developments, we must be clear: law alone will not solve the environmental conflicts and challenges we face. A year after the historic ruling on the Atrato River, many defenders of this river were being threatened and some had been killed for their attempts to reclaim it. As in Guatemala, these communities suffered greatly during the armed conflict and continue to do so.

Our dialogues with Q’eqchi’ elders on the current crisis require us to reflect deeply on our relationship with our natural environment. In effect, they put a mirror in front of us: is it time to wake up and recognize the interrelationship of human beings with the other non-human elements that inhabit the planet? How would the planet, the only home we have, look if we treated all the natural elements – water, earth, air and fire – with the same respect and dignity with which we treat our loved ones?

THE AUTHORS AND THEIR “ACADEMIC RIVERS” IN Q’EQCHI’ AND POQOMCHI’ TERRITORY

Rachel Sieder is research professor in CIESAS, Mexico City and associate researcher at the Chr. Michelsen Institute in Bergen Norway. She is part of the international advisory board of the RIVERS project. She first visited Q’eqchi’ and Poqomchi’ territory in 1995 when she went to Cobán for postdoctoral research on indigenous law and the impacts of the armed conflict. She came to know the region of Nimlaha’kok with missionaries of the Congregación del Corazón Inmaculado de María, who were supporting projects to strengthen councils of Q’eqchi’ elders and the memorialization of those who perished in the armed conflict. She learnt much about Q’eqchi’ worldviews, based on a concept of the sacred which extends to everything, and a great care and reverence for territory and community. In recent years she has worked with the Indigenous Mayoralty in Santa Cruz del Quiché in defense of their own forms of law, including the elaboration (together with Carlos Y. Flores) of the documentary films K’ixb’al and Two Justices: https://vimeo.com/user11226723. She has also worked with the Association of Mayan Lawyers to support different legal cases in defense of the collective rights of indigenous peoples, particularly indigenous women. Her most recent book is Acceso a La Justicia Para Mujeres Indígenas En Guatemala: Casos Paradigmáticos, Estrategias De Judicialización y Jurisprudencia Emergente (2019, Nim Ajpu). Her publications can be found at www.rachelsieder.com

Lieselotte Viaene is professor in the Department of Social Sciences at the Carlos III University in Madrid. She had her first encounter with Q’eqchi’ people in 2002 when she undertook fieldwork for her MA in Anthropology on the role of restorative justice in post-conflict contexts. She accompanied two members from the NGO ADICI, including Manuel Paau (deceased) who was also an aj ilonel or healer, on a 6-day visit to the region of Chama Grande. In this first journey she was invited to all the ceremonies with Paau. Lieselotte has returned to this region over the years, first as part of her doctoral research on indigenous peoples and transitional justice (2006-2010), and later for a legal-anthropological consultancy about the hydroelectric project Xalalá on the Chixoy river (2014-15), and again in 2017 for a comparative study between Guatemala and Colombia about indigenous water epistemologies and human rights to water, financed by a postdoctoral Marie Curie grant from the European Union. She currently leads the project RIVERS – Water/human rights beyond the human? Indigenous water ontologies, plurilegal encounters and interlegal translation(2019-2024) financed by the European Research Council. Her most recent book is: Nimla rahilal. Pueblos indígenas y justicia transicional: reflexiones antropológicas (2019, Universidad de Deusto). Her publications are available at Academia.edu and Researchgate.

Source: Prensa Comunitaria